Cenotes of the Yucatán—Ancient Water Sources on a Parched Landscape

Part 1: What's a cenote?

Hola Amigos! A refreshing dip into a clear cold cenote is amazing and in the Yucatán there are many to explore. Dive right in and discover what these unusual water holes in the Yucatán are.

Tangled green vines brush against my face as I trek behind our guide deeper into the low-lying Yucatán jungle. The narrow, gnarly path—recently cut by machete—oozes damp, musty smells.

It is July, rainy season in Mexico, and temperatures are in the nineties, a veritable heat wave. We’re in search of a cenote, a clear fresh water pool, also known as a sinkhole here in the Yucatán, a place the Maya named Si’an Ka'an or Where the Sky is Born.

An arid land

Although the Maya used these ancient wells as their water source in an arid land that offered few rivers, our search is for recreational purposes. We plan to cool off in the cenote’s crystal waters, to swim and maybe snorkel.

Traipsing through thick forest growth alongside a mangrove swamp, little did I realize this jungle spot forty miles south of Cancun and just seven miles north of Playa del Carmen (Tres Rios) would many years later become a major resort. With a wave of the hand, our guide, Alejandro, motions us to follow.

We ford the stream behind him and enter into a clearing. Now surrounded by brilliant green foliage, the scene becomes a primeval forest. The clarity of the cenote is beyond comparison. Gazing into it I see mangrove tree trunks reaching up from the pool’s bottom, breaking the waterline and stretching high into the tropical sky.

Cenotes are plentiful in this part of Mexico and have become a favorite tourist attraction as vacationers discover they’re an ideal place to cool off in the sultry climate of the Riviera Maya. Close to six thousand are known to exist in the Northeastern Yucatán where Maya civilization flourished for 3500 years from 2000 BC to 1521 CE.

On a parched peninsula, Cha’ac ruled

To the Maya, a culture made great by ruling dynasties and strong religious beliefs, cenotes were more than just a water source. The Maya believed cenotes were the sacred entrance to the underworld of spirits where Cha’ac, the rain god, lived. On a parched peninsula, Cha’ac ruled in a long line of spiritual dieties. Water is life.

Of the Yucatán’s numerous cenotes, perhaps best known is the Sacred Cenote at Chichen Itza, the ceremonial center known for towering pyramids and spring and fall equinox displays of shadow and light. The vertical wall cenote has a diameter of 160 feet and measures 60 feet from its lip to the water surface below.

Made famous by explorer Edward H. Thompson 1, this well brought forth its diabolic history when Thompson dredged it in 1904.

Chicen Itza’s sacred cenote

Though short in the field of archeology, Thompson excelled at research and consumed everything he could find on the ancient Maya. Through research, Thompson understood that Maya life intertwined agriculture, religion and water. Due to agricultural needs to feed a burgeoning population, the Maya calendar was developed to determine auspicious dates for planting and harvesting.

Thompson also knew the calendar was interpreted by the priests, but as their promises failed to bring rain, he’d heard human sacrifices were thrown into the cenote to appease Cha’ac. He was positive that along with the maidens, other offerings would have been made, and he wrote about it in his popular book People of the Serpent: Life and Adventures Among the Maya, in 1932.

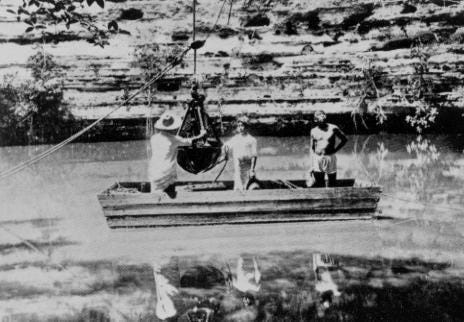

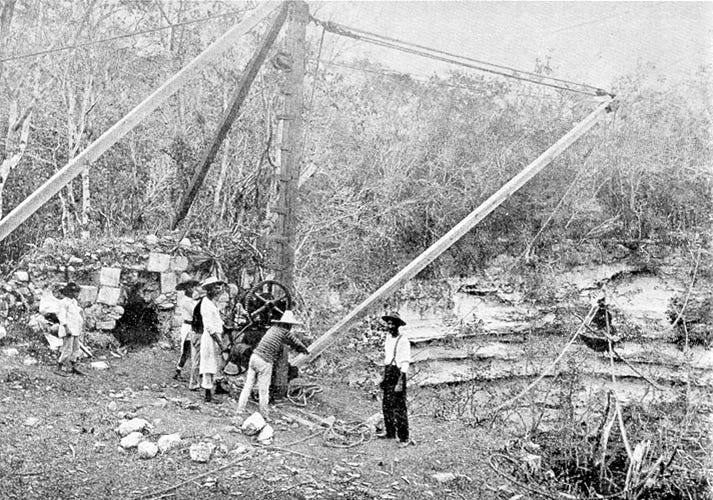

The Boston explorer tested his theory by creating a diving aparatus and taking diving lessons from a Greek diver he hired to assist him. He traveled to Boston to buy a derrick and thirty-foot boom, designed his own diving apparatus, and shipped it all to the Yucatán.

On his return, he dove and dredged the Sacred Cenote daily. Finally, about six weeks in, he came up with gold and copper discs, figures of Maya gods and the clincher, human skeletons. His exploration of the cenote proved that human sacrifice was indeed a part of Maya life, with human sacrifice the key to giving them access to the rain god and his whims.

Chichen Itza's sacred cenote is but one of many in the Yucatán, and the most famous, possibly due to the booty Thompson extracted from it. Though the dredging was in step with the desires of his benefactors, the Archaeological Institute of Yucatan (AIY), funded by the Carnegie Institution, the looting of it didn’t become public knowledge until a savvy reporter for the Hearst Papers, Alma Reed, became privy to it.

Sent by her New York editor to follow the trail of Mexico’s opening a new road to Chichen Itza to promote tourism, Reed arranged to interview Thompson, lead explorer on the project. How did she happen onto this secret, hiding in plain sight? By directly asking Thompson about it.

Thompson confessed to Reed, recklessly divulging he had dredged Chichen Itza’s sacred cenote and had taken gold and jewelry from the sacrificial victims. Astonished by the enormity of his admission, like the true-born paparrazi she was, Reed asked the archeologist to sign a confession. He did.

Now that I’ve intrigued you (hopefully) with these tales from the Yucatán, Part 2 will explore how cenotes were formed due to the Yucatán Peninsula’s distinct geology. I’ll also give details on some of the more prominent cenotes on the Peninsula, if you’re heading to southern Mexico and want to take a side trip for a dip in a fresh water pool—cool and crystal clear and breathtakingly beautiful. Stay tuned.

Edward H. Thompson, People of the Serpent: Life and Adventures Among the Maya. Houghton Mifflin. (January, 1932).

If you’re interested in supporting well-researched and thoughtful writing and are feeling generous, your paid subscription would make my day. Keep up to date on Mexico, travel, chapters from Where the Sky is Born—how we bought land and built a house on the Mexico Caribbean coast. And opened a bookstore, too! All for $5/monthly or $50 per year.

Hit the heart at the top of this email to make it easier for others to find Mexico Soul (to stimulate those pesky algorithms) and make me very happy.

Backstory—Puerto Morelos sits within 100 miles of four major pyramid sites: Chichen Itza, Coba, Tulum and Ek Balam. By living in close proximity to this Maya wonderland we pyramid hopped on our days off from Alma Libre Libros, the bookstore we founded in 1997. Owning a bookstore made it easy to order every possible book I could find on the Maya and their culture, the pyramids, the archeologists who dug at these sites and the scholars who wrote about them, not to mention meeting archeologists, tour guides, and local Maya who popped into the store. I became a self-taught Mayaphile and eventually website publishers, Mexican newspapers and magazines, even guidebooks asked me to write for them about the Maya and Mexico. I’ll never stop being enthralled by the culture and history and glad there’s always new news emerging for me to report on right here in Mexico Soul. Please share this post if you know others interested in the Maya. Thank you!

Thanks for the restack, Emese!

Whaaa? How could one dredge a cenote? They're all networked, no? Water would cascade in as fast as he dredged it out.

Me: Maybe he brought a bunch of large corks.

Me (v2): Maybe this cenote isn't networked, Damon. Duh.

The looting is barely as incredulous as the signed admission that he did it! Holy Cha'ak!