Chocolate's Ancient Ties to Maya Mexico and Its Troubling Future

Today's plight to find sustainable cacao sources as trees diminish worldwide

Hola Amigos! We’ve all had chocolate cravings—as kids at Easter waiting for the Easter Bunny, maybe Valentine’s Day or Halloween. Some of us have outgrown it, others have grown fonder of it. But where does chocolate come from? My question was answered by a famous Mayanist-authority on pre-Columbian civilization and his research-enamored anthropologist wife: Michael D. Coe and Sophie D. Coe. Their research (and subsequent book) is the ultimate in our search for chocolate’s origin. Also, read about the world’s diminishing ability to source out cacao from Ruth on Planifolia Substack, who in her 30-year career went from trading cacao to growing it. Today she farms cocoa (cacao) and vanilla using regenerative agriculture in Belize.

The jury’s in on chocolate’s origin, that devilishly addictive treat like no other. It came from Mexico. But the exact location has been questioned by more than a few. Is it Oaxaca? Central Mexico? The Yucatán?

Though many have claimed it, anthropologist and food historian Sophie Coe knew it, studied it, and wrote about it in The True History of Chocolate. 1In her very readable book, Coe draws on botany, archeology, and culinary history to present chocolate's complete and accurate beginnings.

"Essential reading for anthropologists as well as scholars, Coe's book brings serious pleasure reading to lay readers who are cooks, eaters, and students of food ways," said a review in American Anthropologist.

Culinary anthropologist, food historian

Sophie Coe's interest in the food and drink of pre-Spanish peoples of the New World inspired her to write America's First Cuisines in 1994. 2 During that research, she discovered the important position given to chocolate in Mesoamerica. She first became fascinated with chocolate's history in 1988 while preparing a paper titled "The Maya Chocolate Pot and Its Descendants" for a seminar.

Unfortunately, Coe died before the book was finished. With thousands of pages of reference amassed and the first eight chapters outlined—so near and yet so far—she couldn’t complete the task. Her husband, famed archeologist and pre-eminent Maya scholar Michael D. Coe, promised her he would see it through to publication.

Michael Coe steps in

In the book’s introduction, Michael Coe explains that writing about food and drink only become a 'respectable,' scholarly subject in recent decades. As a consequence, early on, culinary history was left to amateur enthusiasts who usually promoted one food, drink, or cuisine.

Sophie’s book is fascinating because as a culinary anthropologist, she looked at her subject with a worldwide view. And along with husband Michael Coe, archeologist, we the reader could not have a better pair to guide us through the fascinating world of cacao and its origins.

Sophie, a researcher’s researcher, spent hundreds of hours in both American and European libraries tracking down all possible references to chocolate and cacao as well as vast amounts of time in her husband's enormous Mesoamerican home library. With her scientific background and a doctorate in anthropology, she left no stone unturned.

Sophie went right to the sources. “Her idea of heaven was working in an ancient library like Biblioteca Angelica in Rome, turning the pages of 400-year old books, in search of chocolate data,” wrote Coe in the preface of the book he co-authored (posthumously for Sophie).

After her death in 1994, Michael continued to organize her notes. Even though some chapters were outlined, the book wasn’t published until 2003. The second edition, 2013, bore a wealth of new information on cacao and chocolate and its place in ancient Mesoamerican cultures, thanks to the recent decipherment of Maya hieroglyphic texts.

Cacao found in burial sites

One thing determined in the decade between the book's first and second editions was that the royal occupants of every Maya tomb went to the next world accompanied by Mesoamerica's most revered drink.

We know this due to recent pyramid excavations that gave archeologists insights into how important chocolate was to these civilizations.

Finicky cacao

The cacao tree, Theobroma cacao, is picky. It refuses to bear fruit outside a 20 degree latitude north or south of the equator. Nor is it happy if the altitude is too high—then it will shed its leaves. It's a magnet to rodents of all kinds who steal the pods for the sweet white pulp.

It’s a botanical problem child. It gets diseases: pod rots, wilts, and fungus produce extraneous growth called witches' brooms. It takes three years to bear fruit. It was first thought it needed the shade from taller trees, but cacao also needs litter on forest floors of old leaves, dead animals, and rotten pods to create a rich soil base.

The young pods, green in color, can turn yellow, red, or remain green when ripe. They cannot open on their own and need humans or animals to assist. Animals are drawn to the pulp surrounding the acidy bean, and break the bean out of its shell for the meat.

It takes four steps to produce cacao 'nibs' or kernels so that the beans can be ground into chocolate: fermentation, drying, roasting or toasting, and winnowing.

For three thousand years, this is how the production has gone, wrote the Coe’s.

Cacao’s roots

Though not one hundred percent certain, it's thought this cacao species, Theobroma, originated in the Amazon River Basin below the slopes of the Andes. Researchers don’t believe it was used by South Americans. It's thought they transported it as an already domesticated plant from South America to Central America and Mexico, with the discovery of the intricate chocolate process made by Mesoamericans.

Columbus’ encounter

It's well known that the first European encounter with cacao took place on Columbus' fourth Atlantic voyage when his son Ferdinand came across a Maya trading canoe with cacao beans in its cargo in 1502.

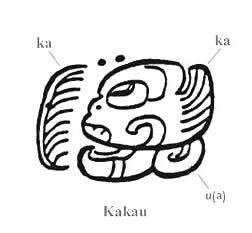

Coe states it was known that chocolate was used among the Aztecs both as a drink and currency. And, he writes, Spanish invaders derived their earliest knowledge of cacao, and the word cacao, not from the Aztecs but from the Maya of the Yucatán and neighboring Central America.

In fact, one thousand years before the Spaniards landed on their shores, the Maya were writing ‘cacao' on magnificent vessels used in preparation of chocolate for their rulers, both living and dead.

The Olmec connection

But before the Maya, there were the Olmecs. Their complex culture flourished in Mexico's Gulf coast lowlands about 1500 to 400 BCE. Prodigious builders of massive ceremonial centers, they left behind their famous colossal stone heads along with exquisite jade carvings.

Sadly, they left behind no writings that ethnographers could decode. Linguists did decipher an ancestral form of a family of languages, Mixe-Zoquean, still spoken by thousands of peasants today near Olmec lands.

At the height of their influence, scholars believe the highly civilized Olmecs used 'loan words' to communicate with other cultures. These are still in use to this day.

One of those loan words is cacao, from the Mixe-Zoquean language, and originally pronounced kakawa.

So, Coe continues, the Olmecs possibly either first domesticated the plant or discovered the chocolate process. Hershey Foods, U.S. chocolate candy manufacturer, got involved with chocolate's history by scraping archeological ceramics used for liquids and detected alkaloids found in Theobroma cacao as far back as 38 centuries, which pre-dates the Olmecs.

Excavations show an early pottery producing culture, the Barra—pre-Olmec— dedicated sophisticated neckless jars, so delicate they must have been used to display valued drinks rather than for cooking. Radio-carbon dates were from 1800 to 400 BCE. Some of the pieces found the compounds or alkaloids of cacao.

Excavators for Hershey's lab found a stone bowl in San Lorenzo (Olmec) region dating to 1350 BCE that was positive for theobromine, meaning the Olmec kingdom knew of chocolate, had a Mixe-Zoquean word for it, and could well have been adapted from another emerging culture in Mesoamerica, eventually passing that cacao knowledge to the Maya. What a long and winding road.

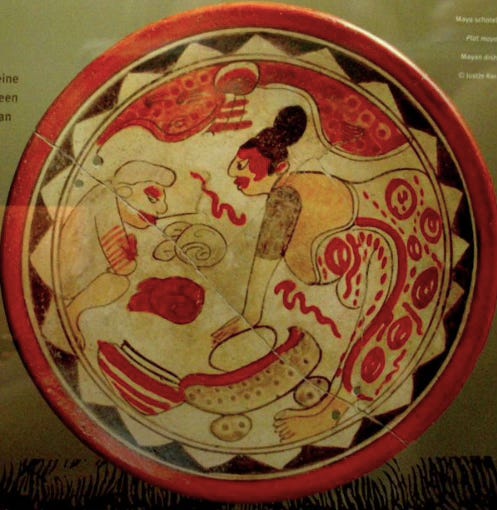

The Maya not only consumed the chocolate but revered it. Maya written history and art displays chocolate drinks being used in celebrations and to finalize transactions. Carvings on pots discovered in royal burial tombs show drawings of a drink being prepared, undoubtedly chocolate.

A Maya tradition

Despite chocolate's importance in Maya culture it wasn't reserved for the wealthy but was readily available to anyone. Before the Spaniards arrived in the New World, it was prepared as a drink, gruel, powder, possibly even a solid substance. In many Maya households, it’s believed chocolate was served with every meal. When used as a hot drink it was thick and frothy and combined with chili peppers, honey, or water. They also liked foam in their chocolate, not unlike a fine cappuccino, and created it by pouring the liquid from one vessel to another like a Starbucks barista.

A gift from the gods

The Aztecs took chocolate admiration to another level. They believed it was a gift from their gods. Like the Maya, they enjoyed the caffeinated kick of hot, cold and spiced chocolate beverages served in ornate containers.

Both the Aztec and the Maya used the beans as currency, and in Maya culture, cacao beans were considered more valuable than gold.

For Aztecs, it was an upper class extravagance, and Moctezuma II supposedly drank gallons each day for energy and as an aphrodisiac. It's said he also reserved some beans for his military.

Cortés and chocolate

Cortés was introduced to chocolate at Moctezuma's court. After returning to Spain, cacao beans in tow, he supposedly kept his chocolate knowledge a well-guarded secret. One story claims that friars in 1544 brought cacao beans as a gift to Phillip II of Spain. No matter how chocolate got to Spain, by the late 1500s it was a much-loved indulgence by the court. Spain began importing chocolate in 1585.

By 1639, a colonial source said of Mexico, "The business of this country is cacao."

Given the dry climate of the Yucatán, which is unsuitable for cacao cultivation, the Yucatec Maya learned how to grow cacao trees in the damp environment of cenotes, and the Spanish hacendados saw cacao pods dangling from sinkhole roofs in a form of 'silvi-culture.'

Europe goes crazy for chocolate

Though it took a while for the European palate to embrace chocolate due to Spain’s well-kept secret, Europeans finally got a taste of it while Phillip II was king. With chocolate the highlight at his daughter's wedding to Louis XIII of France, her gift to her husband was, unsurprisingly, chocolate.

Drinking hot chocolate became a fashionable trend in France before spreading throughout Europe. It's craze was nudged along by a pirate-botanist, William Hughes, who’d spent time in the New World. A natural historian, he began to document plants and the foods he came across. In 1672 he wrote the New World’s first plant book, The American Physician. In it he outlined a recipe for hot chocolate.

Chocolate was ready for its close-up. And for the past 400 plus years, its popularity has skyrocketed. So we can thank the Olmecs, the Maya, the Aztecs, the traders and growers and marketers of chocolate for our long love affair with a delectable and lovely treat.

Chocolate today

Fast forward. Fellow Substacker Ruth, Planifolia, originally from Australia, studied Soil Science at university in the 80s, was a commodity trader for nearly 30 years trading sugar, cocoa, and coffee on three continents, and since 2016, farms cocoa and vanilla in Belize using regenerative agriculture.

In her Substack, ruthmoloney.substack.com, she explains where today’s cocoa comes from. West Africa (specifically the Ivory Coast and Ghana) produce and export more than 70 percent of the world’s cocoa. 3

Unfortunately, at a recent cocoa sustainability conference, she learned the Ivory Coast has several unsolvable problems, including a swollen shoot virus that’s rampant throughout the groves. After 30 years of declining tree maintenance in general, and now with the virus, it’s unlikely they’ll make a long term recovery, she writes.

This should come as no surprise. For years, industry experts have been predicting diminishing yields of cocoa due to poor crops in West Africa along with a steady demand. In addition to the virus, other issues exist. In Ghana, there’s illegal gold mining—much more lucrative than cocoa. And in the Ivory Coast, the average Ivorian farmer is 60. Many are giving up and switching to rubber production, and their children have no desire to continue farming.

On the manufacturing side, chocolate makers have responded by shrinking pack size, layoffs, and switching focus to sugar candy.

Ruth has been part of the cocoa industry since 2004. She’s building a sustainable agroforestry model in Belize based on cocoa and vanilla using her own resources. She has skin in the game, and believe me, every chocolate lover in the world wishes her well.

Sophie D. Coe, Michael D. Coe. The True History of Chocolate. Thames & Hudson. First edition, 1996.

Sophie D. Cole. America’s First Cuisines. University of Texas Press, First edition. March, 1994.

Ruth @ Planifolia. “It’s not our fault, and we can prove it to the 10th decimal place.” (February 10, 2025).

And if you’re interested in supporting independent journalism and writing, please consider a paid subscription to Mexico Soul. This is a free newsletter. I don’t paywall any of my posts, but you can choose to pay if you like what I deliver. It would mean the world to me and will keep you up to date on my posts and chapters from Where the Sky is Born—how we bought land and built a house in a small fishing village on the Mexico Caribbean coast. Not to mention a bookstore, too! All for $5/monthly or $50 per year.

If you enjoyed this article, please remember to hit the heart button to like it.

MY BACKSTORY—Puerto Morelos sits 100 miles from four major pyramid sites: Chichen Itza, Coba, Tulum and Ek Balam. Living in close proximity to this Maya wonderland made it easy to pyramid hop on our days off from Alma Libre Libros, the bookstore we founded in 1997. Owning a bookstore made it easy to order every possible book I could find on the Maya and their culture, the pyramids and the archeologists who dug at these sites and the scholars who wrote about them. I became a self-taught Mayaphile and eventually website publishers, Mexican newspapers and magazines, even guidebooks asked me to write for them about the Maya and Mexico. I’m still enthralled by the culture and history and glad there’s always new news emerging for me to report on right here on Mexico Soul.

Thanks for restack, Denise!

Fabulous post as always, but this one is particularly "sweet"! 🍫 🫕 🍩 🍪