The Fall of Mexico's Mennonites— From Farming Success Story to Forest Pillager and Cartel Courier

Part 1: Mennonites' Mexico history from agriculture to cartels

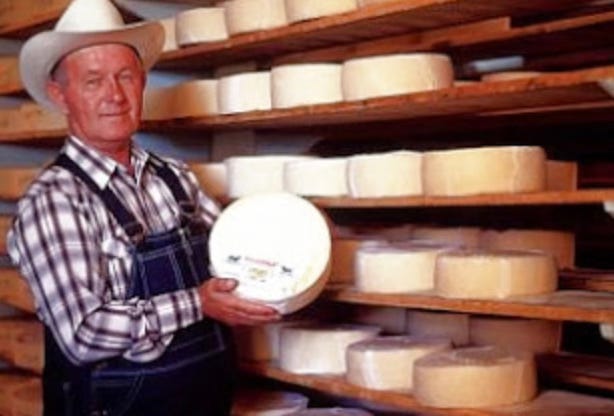

Hola Amigos! From our earliest days in Cancun we’d see Mennonites in the heart of the city, selling cheese wheels. No one seemed to know how the religous group chose Mexico, but it was rumored they had ranches in the countryside, farmed, raised animals and lived off the land by selling dairy products in town. It wasn’t until much later that the religion began to get press coverage, for all the wrong reasons. I’ve broken this article into two parts—there’s a lot to tell you.

In Cancun it’s not uncommon to see Mennonites in straw cowboy hats hawking cheese wheels at downtown stoplights. Smack dab in the middle of a thoroughfare, young men in bib overalls stand fearlessly on the center line, waving their products as cars zoom by on either side. I learned the Mennonites have a long history with Mexico and the Yucatán stretching back to the early 20th century.

And in northern Mexico’s state of Chiuahua, in 1921, at the invitation of President Álvaro Obregón, the settlement of Canadian Old Colony Mennonites helped reconstruct the region's agricultural economy following the Revolution of 1910.

The Mennonites trace their roots to a group of Christian radicals who emerged during the Reformation in 16th century Germany. They oppose both Roman Catholic and Protestant religions and maintain a pacifist lifestyle. Since the 1700s, they’ve been on the move, averting military conscription and mandated public education, while also seeking fertile land for farming. To preserve their faith they emigrated first to Canada.

Maya forest

According to Global Forest Watch, a non-profit that monitors deforestation, the Maya Forest is shrinking annually by an area the size of Dallas. In Campeche, the Mennonites had bought and leased tracts of jungle land for farming, some from local Maya.

In 1992 Mexico legislation made it easier to develop, rent or sell previously protected forest, increasing deforestation and the number of farms in the state. When Mexico opened up the use of genetically modified soy in the 2000s, Mennonites in Campeche embraced the crop and the use of Round Up, a glysophate weedkiller, designed to work alongside GMO crops, according to Edward Ellis, a researcher at Universidad Veracruzana. Local Maya criticize the use of pesticides as it puts bee colonies at risk.

Higher yields meant more income to support large families. For the Mennonites, a family of ten children is not uncommon. They typically live simple lives supported by the land and choose to go without modern-day amenities such as electricity or motor vehicles, as dictated by their faith.

But in dubious contrast, their farm work has evolved to use harvesters, chainsaws, tractors. While most Mennonite communities remain in Chihuahua, 8,000 Mennonites arrived in Campeche in the Yucatán in the 1980s.

Presently the tide has turned on deforestation in Mexico and both ecologists and the government that once welcomed the Mennonites' agricultural prowess believe the rapid razing of the jungle by these new ranches is creating an environmental disaster. The Maya Forest is one of the biggest carbon sinks on the planet as well as the habitat of endangered jaguars. Another hundred species of mammals find the Maya Forest their home.

Deforestation matters

A 2017 study published by Universidad Veracruzana showed that properties cleared by Mennonites had rates four times higher for deforestation than other properties. In the last 20 years, nearly one-fifth of the state’s tree cover has been lost. Less forest creates less rainfall capture.

Under international pressure to follow a greener agenda, the Mexican government persuaded some Mennonite communities to sign an agreement to stop deforesting the land. But not all communities have signed such an agreement.

While speaking to Reuters, a Mennonite school teacher in a pueblo on the edge of the forest stated that the agreement has not impacted the way they farm. The Mennonites have hired an attorney who believes they are being targeted by the Mexican government due to their pacifist beliefs while other land destroyers are not bothered.

Between 2001 and 2018, in the three states that comprise forest growth in Mexico, 15,000 square kilometers of tree cover was razed, roughly the size of the country Belize. With changing weather patterns and less rain, harvests are smaller in general for all concerned, both Mennonites and the Indigenous Maya.

Paperwork concerns

The Campeche Secretary of Environment, Sandra Loffan, clocked in stating the Mennonites did not always have the correct paperwork to convert forest land to farm land. An agreement was signed in 2022, to create a permanent group between the government and Mennonite communities to deal with land ownership and rights, and disagreements that arise including those from locals stating the Mennonites are abusing logging rights.

This, however, is but one of the Mennonites' problems in Mexico. Ten years ago connections between the community and Mexican cartels were exposed when a mule pipeline from Chihuahua to Alberta, Canada, was discovered.

Cartels and marijuana

In this unlikely alliance, the pacifist Mennonites were growing tons of marijuana for the cartels and shipping it north, smuggling it in gas tanks, inside farm equipment and cheese wheels. For background, in an old ABC interview, Michael LeFay, Immigration and Customs Director in El Paso, stated a Mennonite network emerged long ago. What began with marijuana expanded into cocaine smuggling.

When customs officials at the US border looked into a car and saw Mennonites, he explained, officials waved them through. Mennonites were a common sight at the border and frequent travelers from Mexico to Canada because many Canadians from Manitoba and Ontario have family members in Mexico.

Though the DEA issued a statement decades ago that only a few members of the community had links to violent cartels, facts proved them wrong. In the 1990s not all Mennonite families owned land; they fell on hard times, Le Fay continued.

At the same time the tenets of their faith drew questions from a younger generation raised in Mexico where there was no legal age restriction to buy alcohol or cigarettes. Vices began to creep in. It wasn't uncommon, the ABC newscaster reported, to see young Mennonite teens drinking Corona and smoking cigarettes after a Sunday church service once their parents left the church parking lot.

Smuggling charges

Reports started to trickle in: A Mennonite man was accused of smuggling 16 kilos of coke across the US-Canadian border in 2012. Jacob Dyck faced charges of importing $2 million USD of cocaine and possession for purpose of trafficking. The seizures were the result of a 15-month cross-border investigation.

Then along came the Canadian TV drama Pure, about Mennonites connected to the cartels. DEA agents still couldn’t get their heads around it, tsk-tsking the idea that Mennonites had a corrupt streak. DEA Agent Jim Schrant was quoted as saying a "large scale marijuana and cocaine distribution group run by Mennonites with cartel connections seemed bonkers."

Though Schrant was aware that a huge drug distribution group was operating in Mexico and shipping large quantities into the US, he believed it was being run by a few individuals. Then along came Grassy Lake, Alberta, a rural town of 700 that was outed as the distribution hub for an international weed and coke smuggling operation linked to the Juarez Cartel. Eighty percent of town residents are Mennonites. The DEA finally capitulated.

Anti-government sentiments

A widely publicized case against Abraham Friesen-Rempel, 2014, had the DEA intercepting 32,500 phone calls believed to be linked to Juarez Cartel drug activity. Although Friesen-Rempel played only a minor role as driver, he'd delivered 1575 pounds of pot for the cartels. Convicted of smuggling drugs, he received a 15-month federal sentence. This was the warning shot fired over the bow.

It's believed that the cartels lean on the Mennonites because they share a common bond of anti-government sentiment. Staunchly private, the Mennonites shun government interaction and their fierce sense of privacy aligns them with the cartels who share the same philosophy. Also, for decades Mennonites never got a second look at the border. They were the perfect cover for border crossings.

Along with drug smuggling charges, they’re also embroiled in problems with the government’s environmental and ag statutes. The government is extremely dissatisfied with the excessive deforestation due to their farming techniques. Locals also admonish their logging practices.

A few years ago, Mexico's former president Andres Manuel Lopez pressured them to shift to more sustainable practices, with the government planning to phase out glysophate by 2025 which would lower harvest yields and their incomes.

"That's a consequence all farmers, Mennonites and locals, might have to pay to save the environment," said Campeche's Secretary of Environment Sandra Laffon.

And whether the Mennonites plan to play by the rules? Stay tuned.

PART 2: The Mennonites’ slow slide into corruption, coming soon.

RESOURCES:

Cassandra Garrison. “God’s will or economical disaster? Mexico takes aim at Mennonite Deforestation.” Reuters. (July 12, 2022).

Edward Ellis, Romero Montero, José Arturo. Ideas Economic Literature Abstract. “Private Property and Mennonites are major drivers of forest cover loss in central Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico.” (2017).

Editorial staff/AP-Denver. “Mexican Mennonite sentenced to 15 months for marijuana smuggling.” The Guardian. (December 1, 2014).

And if you’re reading this every week and enjoy the creative oxygen it brings, please upgrade to paid! All for $5/monthly or $50 per year.

MY BACKSTORY—Puerto Morelos sits 100 miles from four major pyramid sites: Chichen Itza, Coba, Tulum and Ek Balam. Living in close proximity to this Maya wonderland made it easy to pyramid hop on our days off from Alma Libre Libros, the bookstore we founded in 1997. Owning a bookstore made it easy to order every possible book I could find on the Maya and their culture, the pyramids and the archeologists who dug at these sites and the scholars who wrote about them. I became a self-taught Mayaphile and eventually website publishers, Mexican newspapers and magazines, even guidebooks asked me to write for them about the Maya and Mexico. I’m still enthralled by the culture and history and glad there’s always new news emerging for me to report on right here on Mexico Soul.

Thanks for restack @Tinashe D. Ndhlovu

I’ve seen how complex the line is between survival, tradition, and legality can be here. Isn't it both interesting and shocking that policy decisions often overlook the deeper realities of rural and Indigenous life... Or maybe it's not shocking. Not any more...