Sacred Waters at Risk: The Delicate Balance of Cenote Conservation

Part 2: Understanding cenote history and current environmental risks

Hola Amigos! To the Maya civilization, cenotes were not merely water sources but sacred gateways to the spiritual realm, a place to commune with Cha’ac, the Rain God. And on a parched peninsula, water is life. With few above ground rivers to provide water, Cha’ac ruled. Today we delve into the geology of cenotes and also their fragility in a changing environmental world.

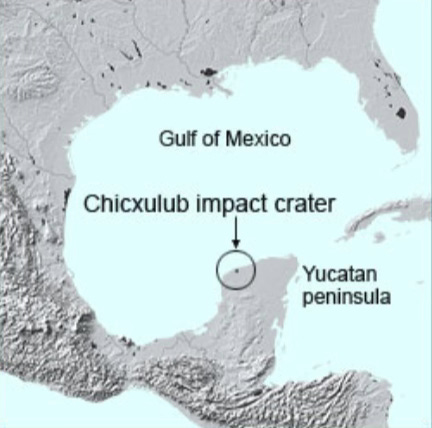

It took an asteroid hurtling at the Earth 66 million years ago, smashing into the Yucatán Peninsula north of Merida in Chicxlub, to establish an ecosystem that created cenotes. And along the way, the effects of that asteroid decimated the long-living dinosaurs. Allow me to explain.

According to geologists, the Yucatán Peninsula emerged as a vast coral reef from that smash-up 66 million years ago, after said asteroid crashed into Earth.

The result created the Chicxulub Crater, 1 dramatic climate change, the end of the dinosaurs, and the emergence of cenotes—underground sinkholes—filled with fresh water.

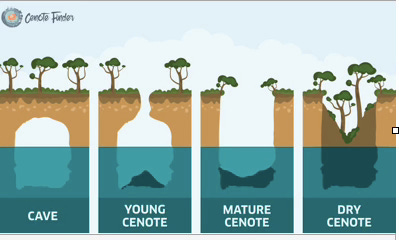

As the oceans receded, mollusks died, creating the limestone shelf that now covers the Peninsula's porous land. Rain waters filtered down into the substructure and created underground rivers. After the last Ice Age, the oceans rose to their current levels and flooded the caves left by the lacy limestone shelves, collapsing some, and creating sinkholes in Yucatán. Though not unique to the Yucatán, cenotes are fairly uncommon geological formations and they can vary considerably in shape and size.

Part of the Yucatán Platform, which is a large chunk of land partially submerged underwater, the Yucatán Peninsula is the portion above the water.

Although cenotes are plentiful in the Yucatán, with thousands known, possibly 10,000, exploring them is a fairly new phenomenon. In the 1980s, geologists identified 21 variations and have since narrowed these down to five basic types: Open air, angled wall, vertical wall as at Chichen Itza, cavern pool with stalactites, and underground domed.

Cave systems

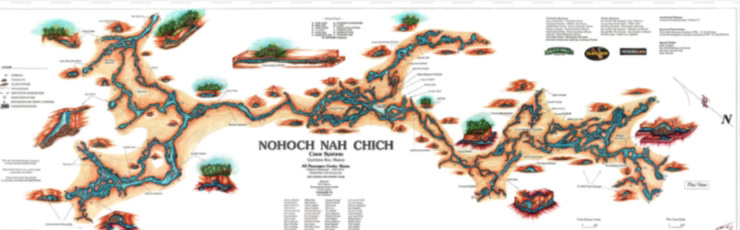

Some cenotes have small surface openings but unfold into an intricate cave system that can literally run for miles. This type is popular with cave divers and tackled by professionals like diver Mike Madden, formerly of Puerto Morelos.

Madden did some of the first explorations near Tulum, Quintana Roo, under the auspices of CEDAM (Club de Exploraciones y Deportes Acuaticos de Mexico) earning a spot in the 1988 Guinness Book of World Records for documenting the world's longest underwater cave system—168,400 feet in all—called Giant Birdhouse or in Mayan, Nohoch Nah Chich. Madden's explorations proved that an intricate series of meandering underground waterways exists, connecting cenote to cenote.

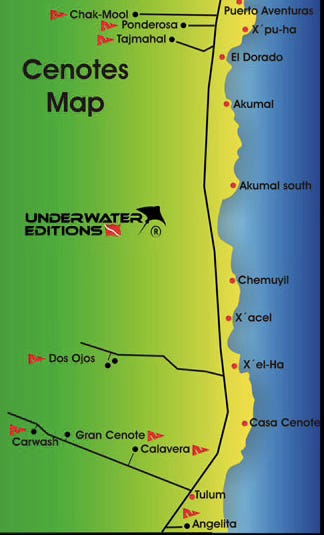

Though considered the world’s most dangerous sport, cave diving has gained in popularity and it's not uncommon to bump into serious divers on Yucatán's cenote route. A handful of popular cenotes are shown here.

Cenote Zaci is in Valladolid, 28 miles east of Chichen Itza. Known as a cavern pool, it’s popular with swimmers and can be crowded at times. At 150 feet wide, its turquoise waters show off stalactites. There’s a wooden walkway around the entire cenote, to better view the massive pool and an adjoining restaurant lights the area at night on an expansive deck overlooking the fresh water pool.

Most photographed cenote

Four miles south of Valladolid off a narrow, two-lane road is Cenote Dzitnup. An underground cenote with angled walls, it has a hole in its ceiling where sunlight streams in at mid-day. Tree roots stretch down from the rocky ceiling to reach the clear, still waters below. Though one of the most photographed of Yucatán's cenotes, with a steep slippery descent leading into this underground cavern, we nearly missed the humble wooden sign announcing it.

Ten miles north of Merida, Yucatán's capital made famous for manufacturing Panama hats at the turn of the 20th century, Xlacah Cenote can be found at the Dzibilchaltun ruins. A popular cooling off spot, this open air cenote is not connected to any underground pools and seems more like a local swimming hole than a cenote.

Dos Ojos Site of Amazing Caves IMAX

Leaving Yucatán and entering Riviera Maya territory, cenotes dot Highway 307 south of Playa del Carmen, 42 miles from Cancun. Dos Ojos, south of Playa, was the site of the Amazing Caves IMAX diving film, 2001. The film shows stunning footage of underground caverns with stalactites and stalagmites. It’s available on Apple TV.

Aktun-Chen combines both a cenote and the area's largest caves within a massive rainforest park, ten miles north of the Tulum pyramids. A bit further south at the Coba pyramid turnoff, Car Wash Cenote is located on a road dotted with sinkholes. A wide pool, unspectacular at first sight but good for swimming, Car Wash opens into an underwater cave where freshwater tropical fish cruise alongside turtles.

And close to Puerto Morelos, there’s Ruta de los Cenotes, on a long stretch of road heading west to Leona Vicario south of town, known as “jewels in the jungle.” Local guides can take you for an all day tour.

Southern cenotes

Heading south to Belize, Cenote Azul is located in Bacalar, 25 miles north of QRoo's capitol, Chetumal. Situated near Bacalar's famous Lagoon of the Seven Colors, the second largest fresh water lake in Mexico, Cenote Azul is Mexico's largest cenote. Stretching 600 feet in diameter, this stunning turquoise-colored cenote is a perfect spot for a swim.

This vast peninsula, comprised of low scrub jungles and white sand beaches, was considered "the most savage coast in Central America" only 60 years ago. Known as Quintana Roo, it was a territory until 1974 when it became Mexico’s 31st state.

In writing about the Yucatán and Mexico’s natural beauty, like cenotes, it’s impossible to not mention the 1.3 million acre Si’an Ka’an Biosphere Reserve established in 1986. In tandem with the region’s biodiversity, cenotes are but a portion of the Yucatán Peninsula’s natural gifts.

Si’an Ka’an Biosphere Reserve

Si’an Kan Reserve covers one third of Mexico’s Caribbean coast. Named a World Heritage site by UNESCO, the biosphere encompasses hundreds of species of local birds, plants, mammals and fish along with acres of mangroves, and lagoons.

Local guides can take tourists to the biosphere reserve or on cenote adventures. The biosphere’s rough 55 kilometer sascab road leads to a dead end at Punta Allen and is frequently impassable.

BE AWARE: No sunscreens, chemicals, make-up and lotions allowed in cenotes as they can impair water quality.

A bleak reality

In spite of these riches, all is not pristine in the cenote world, since former President Andrés López Obrador’s grand Maya Train (Tren Maya) project came into being June 2020. Now a fait accompli (all 20 stations have been up and running at some point since February) environmentalists and conservationists have sounded off on what the 1525 kilometers of track will require in payment from an already fragile environment. Will it be able to withstand tons of weight from trains?

The Riviera Maya, which the train passes through, is the largest jungle in the Americas after the Amazon, and with the train’s arrival, the forest suffered, too. But the most frequent refrain is that AMLO (as the former Mexican president is known) created much of the infrastructure and tracks with lack of geological testing and little transparency.

Fragile ecosystems—millions of years in the making

Environmentalists, archeologists, locals, even the U.N., voiced concern that the railway and its hasty construction would critically endanger pristine wilderness. And nothing was more at risk than the fragile system of cenotes and the underground river system that lies beneath the jungle floor.

The train tracks pass over subterranean caves carved by water from the region’s soft bedrock over millions of years. During train construction, some cenotes were filled in with cement by contractors sinking concrete columns through the caverns to support train weight. In time, it’s feared the cement could contaminate the cenote water system which is still used to this day by local Maya who live in the region, or even pancake the earth’s fragile top layer.

A year ago January, a court in Merida handed down a suspension of the project after it was revealed that steel and cement pilings pierced through a limestone cave roof over underground rivers along an elevated section of railroad south of Playa del Carmen. This 120 kilometer run— most in question—Section 5, passes directly over the famous Sac Actun-Dos Ojos cave system, the second-longest underwater cave system in the world, and Mexico’s largest freshwater aquifer. That court order was eventually put on ice.

In March, 2024, several groups of environmentalists also recorded the damage of installing support pillars to Section 5 in question. They voiced concern over a dozen large holes that had been drilled, some penetrating caves and damaging stalactites. Other pillars have been found leaking detritus into water-filled cenotes, they reported.

In addition, SOS Cenotes and Guillermo D. Christy, photographer, have captured videos which show rusting exteriors and leaking cement believed to be damaging the region’s water supply.

DIVE Magazine’s June 2024 issue 2 writes that experienced divers are well aware of the cenotes’ unique nature. Though some cenotes are little more than holes in the ground, others are doorways into spectacular limestone cathedrals, filled with a growth of stalactites and stalagmites formed over millions of years, virtually untouched by the modern world. Until now.

Cave divers who have explored cenotes’ depths are aware that these unique systems are more than just picturesque spots for a swim. The devastation done by the train’s construction, to both the cenotes and the jungles surrounding the tracks, is only part of the problem, scientists say, and may lead to unfathomable destruction further down the line.

Accident waiting to happen

The Yucatán aquifer’s interconnected systems are at the forefront of problems Tren Maya created for the environment, writes DIVE Magazine. Any pollution entering through damage caused by the railway’s construction may end up flowing through the system until it reaches the coral reefs that surround the coastline of Quintana Roo, from Cancún to Playa del Carmen, and perhaps even to Cozumel. The Great Mesoamerican Reef, the world’s second largest, sits a short distance from the shores of Puerto Morelos.

Christy and diving instructor Pepe (José) Urbina, are the two most vocal opponents of the railway, part of campaign group Cenotes Urbanos, in conjunction with a larger movement, Sélvame Le Tren.

The vast number of support columns that have been drilled into the karst (an area of land made up of limestone) was an attempt to engineer a solution to prevent a catastrophic collapse under the weight of passing trains— because there is no guarantee any individual pillar will sit on solid ground, said Christy.

“The cave system here is in continuous collapse,” Urbina told DIVE Magazine. “They drilled a hole, put the cylinder in the structure and filled that with concrete. The problem with that is that under the limestone—for 200 meters, maybe more—you won’t find any ground underneath—it’s another cave. That’s why they need so many pillars.”

Baby steps by Nat Geo’s Bold ideas program

Although an initiative by a team from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill launched an educational initiative aimed at protecting these unique foundations, funded by National Geographic’s Bold Ideas program, it may be too little too late—a toothless attempt at trying to harness “a developing social awareness in students aged 11 - 14.”

Headed by Anthropologist Patricia McAnany who is spearheading the collaborative project, it’s focusing on engaging local school children as environmental advocates. A good idea, but with no weight in the real world.

A complete unknown

But since summer 2024, little has been written as to the deterioration of the cenotes in question near Playa del Carmen, the leaking support pillars, and the ability for the fragile top layer’s capacity to hold up under the weight of constant tons of moving locomotives day in and day out. The story is still being written.

And the waiting game begins.

If you’d like a list of additional cenotes, let me know and I’ll send you more info.

Jeanine Kitchel. “Where the Dinosaurs Roamed—Chixculub Crater was Site of Asteroid Impact.” Mexico Soul. (May 2, 2024).

Mark “Crowley” Russell. “Below the Line—Mexico’s ‘Tren Maya’ is Destroying Yucatán’s Cenotes.” DIVE Magazine. (July 22, 2024).

If you’re interested in supporting well-researched and thoughtful writing and you’ve been enjoying my posts and are feeling generous, your paid subscription would make my day. Keep up to date on Mexico, travel, chapters from Where the Sky is Born—how we bought land and built a house on the Mexico Caribbean coast. And opened a bookstore, too! All for $5/monthly or $50 per year.

Hit the heart at the top of this email to make it easier for others to find this publication (to stimulate those pesky algorithms) and make me very happy.

Backstory—Puerto Morelos sits within 100 miles of four major pyramid sites: Chichen Itza, Coba, Tulum and Ek Balam. By living in close proximity to this Maya wonderland we pyramid hopped on our days off from Alma Libre Libros, the bookstore we founded in 1997. Owning a bookstore made it easy to order every possible book I could find on the Maya and their culture, the pyramids, the archeologists who dug at these sites and the scholars who wrote about them, not to mention meeting archeologists, tour guides, and local Maya who popped into the store. I became a self-taught Mayaphile and eventually website publishers, Mexican newspapers and magazines, even guidebooks asked me to write for them about the Maya and Mexico. I’ll never stop being enthralled by the culture and history and glad there’s always new news emerging for me to report on right here in Mexico Soul. Please share this post if you know others interested in the Maya. Thank you!

Thank you for this post, Jeanine! Jeff and I were talking about this last January when we saw the train tracks being built. It was mainly the same issue we were concerned about: how can they build this on top of a land that is riddled with underground caves and cenotes? Everyone we talked to was concerned, and against the project; military was everywhere (we assumed to prevent vandalism and stop protests). We saw so much destruction - even just above ground, but we suspected it was much worse underground, and your post proves it. :( I can't see a bright future for the train and the peninsula at this point, unfortunately; I wish awareness was enough to get something done to prevent a total environmental catastrophe... at least it is a start, but it might be too late. On another note, we love those cenotes - and met several cave divers (most often at the Carwash cenotes) who told us about the caves they were exploring underground. So much beauty!

Gorgeous pics...along with fascinating info as usual. I'm hoping for the best but fearing the worst as to the effects of the tren. When will we humans learn?