The Home Stretch—Chetumal, the Belize Border and Mexican Time

Chapter 26: A few hundred miles to go

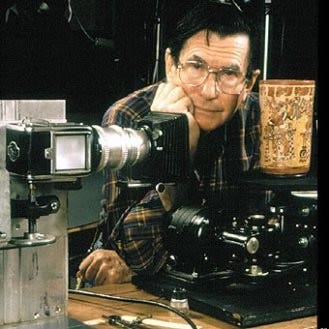

Hola Amigos! The road trip continues! We finally arrived at the southern border of Quintana Roo, only hours from Puerto Morelos. Since this chapter ends our driving adventure and is shorter than usual, I’ve added part of an interview with photographer and visual anthropologist MacDuff Everton, author of The Modern Maya: A Culture in Transition. Though I’ve never met Everton, he used Puerto Morelos as a base over a 40-year period while he wrote about and photographed local Maya. I think you’ll find his story as fascinating as I do.

After the excitement of chancing onto possible antiquity looters at Xpujil pyramids on the lonely two lane road stretching east from Escarcega, we hot-footed it out of the site and arrived at Chetumal, capital of Quintana Roo, around 7 p.m.

Chetumal carried a typical border town vibe—slightly funky, a little seedy, possibly dangerous. It plays neighbor to Belize, not exactly known for a goody two-shoes reputation.

Before NAFTA, the Chetumal-Belize Free Zone was where everyone in QRoo bought household appliances, us included. The zone offered fresh-off-the-boat products from Hong Kong, China and Panama. We’d been there with Joe Marino to take advantage of name brand discounts a few years earlier, so we had a nodding acquaintance with the city.

We’d covered a lot of miles that day and knew we were close to home, but our number one Mexico rule was—Never drive at night. We checked into Los Cocos, one of Chetumal’s nicer hotels, had dinner at the restaurant and returned back to our room by 9 p.m. Time for sleep.

Just as we began our descent into dreamland, we heard a ruckus in the hallway. Then someone flung open the door to the room next to ours and God forbid, it sounded like the hallway crowd was piling in, just a paper-thin wall away.

Oh no. What could be worse than a group of partyers in the adjacent hotel room? Raucous partyers in a border town known for drugs and money laundering in the room next door. Disco music began to blare from a ghetto blaster, accompanied by a round of applause. I dared not knock on their door and ask if they could keep it down. And screaming, “Silencio!” was out of the question. After all, I wanted to wake up the next morning.

Around 9:30 we were in for another treat. The muchachas had arrived. Now, along with the boom boom of the music, an occasional high-pitched squeal could be heard, then intense giggling and infrequent screams.

By 1 a.m. things were leveling off. The music died down. I heard someone fall against the wall, then I heard the door open and a litany of goodbyes were uttered. The girls were leaving. Ojala!

We were out of the hotel the next morning by seven, anxious to be off Mexico’s highways and byways and tucked away in our little fishing village without all this drama. Four hours later we arrived in Puerto Morelos. We’d take on customs later in the week to retrieve our stuff and my books. For the balance of that day, our first as full time Mexican residents, we were off the clock. We were on Mexican time.

Photographer MacDuff Everton and The Modern Maya

MacDuff Everton, photographer and visual anthropologist, is considered a master of panographic photography. His magnum opus, states Wikipedia, is The Modern Maya: A Culture in Transition, which shed light on the Maya people both during globalization and prior to.

Everton has worked with authors Linda Schele and David Friedel, as well as numerous publications, including Conde Nast Traveler, Life, The New York Times, Outside, and Smithsonian magazines, and is a contributing editor at National Geographic Traveler. His public works are on view at the British Museum, Musée de l’Eysée, Museo de Arte Moderna, Bibliotèchne National de France, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

He began his photography career while taking a gap year from high school at 17 to surf in Biarritz but ended up hitchhiking around the world. He’s quoted as saying he “Literally picked up a camera from an American tourist in Denmark. . . who didn’t want to look like a tourist, and by the time I got to Japan, I sold my first two stories: one on Burma, the other on Southeast Asia. It changed my life.” His gap year became a gap decade.

He traveled to the Yucatán and became involved in his Maya project in 1967, and wanting feedback, he went back to his home town, Santa Barbara, and enrolled at UCSB where he dove into academia and got an MFA.

FROM HERE ON—A portion of his December 18 interview in The Independent, Santa Barbara, regarding The Modern Maya and the project.

SB—You have a book called The Modern Maya. What are some of your fondest memories from the Yucatán and living there?

ME—There aren’t many documentary photography projects that span more than 40 years, especially working with the same individuals and their families. This book is their stories. While most history chronicles the famous, this is about the lives of ordinary people who are the soul of their culture.

The Italian reporter Tiziano Terzani wrote, “Facts that go unreported do not exist if no one is there to see, to write, to take a photograph, it is as if these facts have never occurred, this suffering has no importance, no place in history. Because history exists only if someone relates it.”

When I first visited Yucatán, I wanted to do a day in the life modeled on the Life magazine pieces. When I started living with different families, I found their lives so different that a day wasn’t enough to convey what they did. A day became a week, then a season, then a year. After 20 years, the University of New Mexico Press published The Modern Maya: A Culture in Transition. I thought I was through and I could move on to another project.

But so many significant events followed that I realized I had to keep telling my friends’ stories. For example, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) put nearly three million Mexican farmers out of work. For an agrarian culture, this had a devastating effect—so much of Maya cultural knowledge, built up over thousands of years, is connected to their agricultural practices and ceremonies. If they stop farming, they lose the understanding of their relationship with the land that’s built into their farming system.

When young people aren’t learning from their parents in the field—if you skip a generation—that information is lost. Then there are the new Evangelical sects who forbid their members to participate in community activities in which the entire village had always taken part, tearing communities apart.

Tourism became a major industry and monoculture, transforming the Caribbean coastline into some of the most valuable real estate in North America. And at the same time, the narco-traficantes appeared with their drugs and violence.

I had questions about the prevailing hypothesis on the collapse of the ancient Maya. I found an emerging group of botanists, agro-ecologists, epigraphers, archaeologists, and ethnographers studying the ways in which the Maya cultivated and managed their land.

As their separate discoveries are combined, we see just how many widely believed assumptions about the Maya lack nuance or are even incorrect. So, I met with two archaeologists while they conducted their field investigations and talked with them about the hypothesis that environmental degradation led to the collapse of the Maya. What I found starts the book.

People often look to history to find correlations that match their current conditions—so the so-called collapse of the Maya has been blamed on overpopulation, environmental degradation, warfare, revolts, disease, or climatic changes (such as prolonged drought).

But many archaeologists now believe there was a cultural transformation—a profound political, economic, and demographic shift (think Detroit, for a contemporary equivalent of a city abandoned). The Maya voted with their feet. In fact, archaeologists today argue that Maya civilization flourished and even blossomed during the Postclassic period.

My fondest memories are living with my friends in their homes, working with them in the field, telling their stories, and, finally, with the help of my neighbor Isaac Hernandez, translating and publishing it in Spanish so they could finally read it after the two volumes in English, the latest with University of Texas Press, The Modern Maya: Incidents of Travel and Friendship in Yucatán.

SB—What advice would you give to aspiring photographers?

ME—In order to support my visual anthropological work with the Maya, I needed to make money. At first I did construction as a carpenter, the cement work, stone work. But then I started working as a wrangler and packer, eventually running a pack station out of Golden Trout Wilderness, living in the backcountry, on horseback most days. It really helped refine my sense of light and color. I have good peripheral vision because I use it. I know light. I know what the weather might do.

Sitting in a saddle for 16 hours prepared me for when I started getting editorial assignments, flying all over the world, sitting in economy, then landing, renting a car and driving six hours to a location.

My first editor at National Geographic advised me that when I found something really good, really shoot it. Then shoot it six more different ways.

Respect. Respect your subjects. Try to work with editors that respect your work.

Everton, the Shifting Stance on Maya Civilization and Today’s Maya

Everton’s comments touch on the shifting ideology of whether the Maya civilization fell into decline. Though the common rejoinder is that their civilization failed, after mid 900 CE— the Maya Post-Classic period—Chichen Itza, Mayapan and Uxmal actually flourished for several centuries, though Maya lowland cities’ populations waned. This opposing narrative—one of success/longevity—is not mentioned much. But to indicate what an ongoing study the Maya civilization is, roughly every year since their hieroglyphic code was broken in 1976, a new term surfaces to explain why the great lowland cities faltered. The debate is still open on what happened to the ancient Maya.

First came “Terminal Classic,” then “Post-processualsim,” and finally in the 1980s and 1990s, the definition between “collapse” and “decline” was explored.

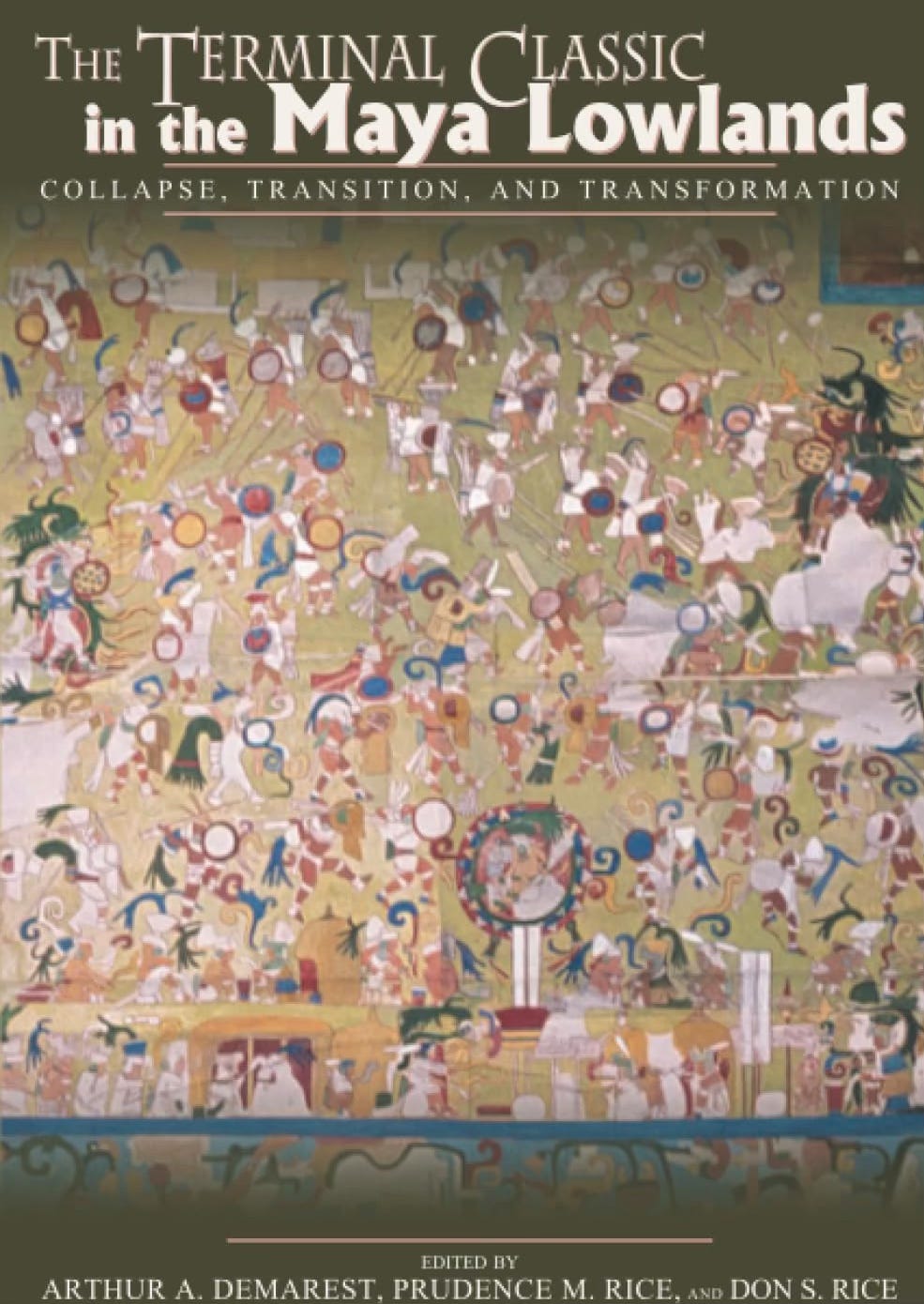

In The Terminal Classic in the Maya Lowlands: Collapse, Transition, and Transformation, authors Demarest, Rice, and Rice explain that while scholars were asking new questions, “The attempts to answer them were consigned to outmoded concepts that no longer yielded insights.”

“Presently the ‘notion of a collapse’ of Maya civilization has been viewed as offensive by some scholars and a few Maya activists, given the vigor of the Maya cultural traditions of millions of speakers of Maya in Mexico and Guatemala today. Both the intellectual concession and political insensitivity can be attributed to careless terminology of what constitutes a ‘transition,’ or ‘decline,’ or ‘collapse.’”

The authors state that rather than using the term Late Classic, archeologists are now considering that these centuries represented a transition, and possibly the beginnings of something new of importance. And rather than speaking of ‘the collapse of a civilization,’ it should be referred to as the end of a great cultural tradition.”

“Clearly, Maya civilization as a general cultural and ethnic tradition—a great tradition—did not experience any collapse or decline. The post classic Maya kingdoms of northern Belize and Guatemala were large, vigorous polities, and the Maya tradition, (with) more than 10 million indigenous citizens of Guatemala and Mexico, is currently experiencing a great cultural linguistic and political flourescense.

“Indeed, this contemporary Maya resurgence is challenging our conception of what is ‘Maya’ and how anthropologists and archeologists view these societies.” 1

The Yucatán Times notes that the interest of locals and foreigners in learning the Mayan language demonstrates that it is a significant approach to recognizing the importance of this culture. 2 Classes are taught at the Municipal Institute for the Strengthening of Mayan Culture in Merida.

Arthur Demarest, Prudence Rice, Don Rice. The Terminal Classic in the Maya Lowlands: Collapse, Transition, and Transformation. University Press of Colorado. (2005).

Editor. The Yucatan Times. “Greater Interest in Mayan Language Courses Offered.” (December 28, 2024).

If you’re interested in supporting well-researched and thoughtful writing and you’ve been enjoying my posts and are feeling generous, your paid subscription would make my day. Keep up to date on Mexico, travel, chapters from Where the Sky is Born—how we bought land and built a house on the Mexico Caribbean coast. And opened a bookstore, too! All for $5/monthly or $50 per year.

Hit the heart at the top of this email to make it easier for others to find this publication (to stimulate those pesky algorithms) and make me very happy.

Backstory—Puerto Morelos sits within 100 miles of four major pyramid sites: Chichen Itza, Coba, Tulum and Ek Balam. By living in close proximity to this Maya wonderland we pyramid hopped on our days off from Alma Libre Libros, the bookstore we founded in 1997. Owning a bookstore made it easy to order every possible book I could find on the Maya and their culture, the pyramids, the archeologists who dug at these sites and the scholars who wrote about them, not to mention meeting archeologists, tour guides, and local Maya who popped into the store. I became a self-taught Mayaphile and eventually website publishers, Mexican newspapers and magazines, even guidebooks asked me to write for them about the Maya and Mexico. I’ll never stop being enthralled by the culture and history and glad there’s always new news emerging for me to report on right here in Mexico Soul. Please share this post if you know others interested in the Maya. Thank you!

This reminded me of our first New Year's Eve in Mexico. We had rented an apt for Russel's mom and kept it an extra day after she returned to San Diego, and we went out to walk the city and enjoy the festivities. It was fairly quiet in town and when we returned. Then the partying started after midnight and continued until dawn, at a small bar right around the corner!

Your hotel story had me laughing - I completely understand those thin-wall nightmares from my own travels! But what really grabbed me was how you connected that real-life drama with the fascinating Maya history bits. It was interesting to read the Maya "collapse" from your perspective. Really makes me want to dig deeper into those stories myself. I look forward to diving into more of your content this year, Jeanine! ❤️